Our Perspective

Detection and Prevention of Money Laundering from Human Trafficking Proceeds Using AI and Machine Learning Solutions

Our Perspective

This paper illustrates the complexity of a human trafficking transactional scenario, highlighting the current technological limitations in identifying this risk and discussing how sophisticated AI technology can be utilized by financial institutions to bridge existing technology gaps.

Financial Institutions (FIs) are constantly developing rules to identify potentially suspicious transactions related to human traffickers. As these money launderers create sophisticated methods to conceal the origin of funds or their identity, it is extremely challenging to expect a rules-based configuration to accurately identify true positives.

Instead, the rules-based configuration generates numerous false positives, which poses a significant burden for the operations team of FIs.

Regulators require FIs to submit cases that are largely meaningless and composed of false positives, leading to fatigue among all stakeholders – including the FI’s operations team and law enforcement agencies. Moreover, this approach often overlooks the actual traffickers or launderers who should be recognized by the institutions.

The primary weaknesses in this detection method are:

A firm operating a laundry service employs over 150 employees and has established a banking relationship with a leading Tier 1 bank.

From the employer's account, one of the employees (Subject A) receives multiple micro-amounts credited throughout the month, followed by various debits that do not align with the employee's profile.

The employer's account (Entity ABC) receives large amounts daily from various external parties. These external entities appear to share the same address within a city, although their bank accounts are located in different cities.

Additionally, Subject A's account experiences multiple credits through a payment app (Zelle) every other day, at the end of the day.

Significant internal transfers of funds occur from Entity ABC's account to another Entity DEF, and subsequently to external payments for various purchases.

Given the many intricacies in terms of credits and debits, the complexity is quite high, making it challenging and cumbersome to apply a risk-based approach to identify potentially suspicious transactions.

Given the sensitivity of this topic, industry practitioners, technologists, and product firms are eager to address this problem by utilizing advanced analytics such as AI, ML, and Network Analysis. Financial institutions are modernizing their technology architecture to integrate AI components, enhancing their existing platform's transaction monitoring capabilities. The AI model will focus on identifying both suspicious transactions and customer profiles, as well as changes in behavior. Inherently, human trafficking is complex due to the nature of its microtransactions; however, it often involves a high volume and multiple related parties throughout the entire life cycle.

The following key signals can be leveraged for predicting AML transactions.

Mapping Observations to Transactions

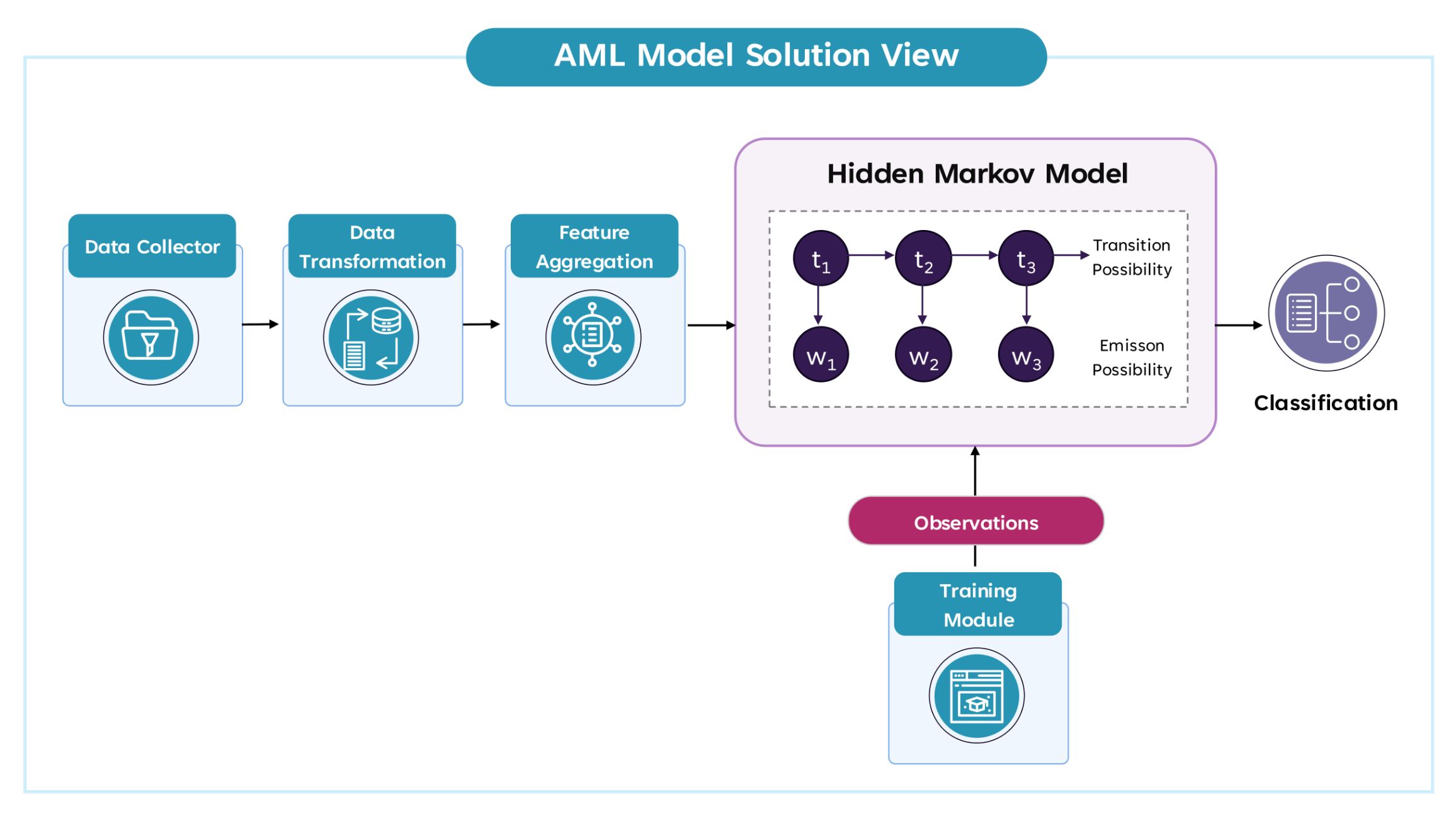

The provided AML models are essentially observations that can be used alongside the HMM (Hidden Markov Model) for training. Here’s how each AML model could be mapped to observable events.

1. Transactions involving pre-paid cards with a focus on merchants associated with human trafficking: This observation could flag transactions involving prepaid card usage at suspicious merchants.

2. Human trafficking networks and activities involving multiple accounts tied to a single party: This may correspond to observations where transactions are linked to multiple accounts, all controlled by a single individual or entity.

3. Transactions to/from countries known for human trafficking: The observable event here would be cross-border transactions to/from countries on specific high-risk lists, such as those cited by FATF or FinCEN.

4. Unusual Payroll/Wage Disbursements: This observation could include payroll disbursements that are rapidly withdrawn in cash, signaling attempts to launder wages.

5. Multiple employees receiving similar payments: This observation may arise when multiple accounts receive identical amounts from a single employer.

6. Payments inconsistent with declared business size/nature: The observations here could consist of transactions that are disproportionate to the business's reported income or nature.

7. Frequent Purchases of Prepaid Cards or Cryptocurrency: This observation indicates an individual or entity purchasing multiple prepaid cards or cryptocurrency, often suggesting layering in money laundering.

8. Wires received from multiple businesses to a single account: A pattern of funds moving from various businesses (like nail salons or massage parlors) into a single account could signify financial concealment.

9. Frequent payments to motels/hotels in red-light districts: This observation might reveal a financial trail leading to specific motels or hotels, especially in high-risk areas.

10. Travel bookings for minors or non-family members: Suspicious booking patterns, such as frequent travel bookings for minors, could indicate human trafficking activity.

11. Accounts with multiple individuals using the same address and phone number: These transactions may be linked to illicit activities if associated with inconsistent KYC documents and employment histories.

12. Multiple accounts under different names but sharing common information: This may indicate a coordinated effort by a money laundering network using multiple aliases with similar contact information.

13. ATM withdrawals made from different locations in short timeframes: Multiple ATM withdrawals across different locations in a short timeframe may suggest an attempt to obscure the source of funds.

Step 1: Data Collection and Preprocessing

The first step involves collecting the transactional data that contains the listed features (attributes) and preprocessing this data for use with the Hidden Markov Model, which applies to human trafficking transactions.

1.1 Collecting Data

The data can be organized in a tabular format, where each row represents a transaction. Each transaction should include the following attributes, depending on whether the trafficker or the victim is conducting the transaction:

1.2 Data Cleaning and Transformation

The data must be cleaned and pre-processed, including:

1.3 Creating Temporal Sequences

Since HMMs are sequence models, you need to convert the transaction data into a temporal sequence format. Each transaction can be regarded as a time step, and for each time step, you would observe multiple features (e.g., amount, merchant, country). To model money laundering behavior, you'll generate sequences of observed transactions for each user or account.

Step 2: Feature Engineering

To make the HMM model work with the attributes effectively, additional feature engineering might be required:

2.1 Feature Aggregation

2.2 Anomaly Detection Features

Identify transactions that may potentially deviate from the norm (such as unusual payroll disbursements or multiple prepaid card purchases in a short time frame) and flag them as additional features.

2.3 Lagged Features

For every transaction, consider previous features that reflect past transactions. For example:

Step 3: Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Setup

Now, let’s configure the Hidden Markov Model with the data, noting that the HMM will learn patterns from sequences of observations.

3.1 Define States in the HMM

State 1: Legitimate transactions.

State 2: Suspicious transactions (initial stage of laundering).

State 3: Advanced money laundering (involves complex networks and fund movements).

State 4: Final laundering stage (cleaned funds proceeding to their ultimate destinations).

These states represent different stages in the money laundering process that we want to detect.

3.2 Define Observations

The observations consist of the features gathered from the transactions. These include multivariate features such as:

Each observation represents the feature vector linked to a transaction.

3.3 Define Transition and Emission Probabilities

We can estimate these probabilities from historical data by utilizing the Baum-Welch algorithm, which is an Expectation-Maximization method for training HMMs.

Step 4: Training the Hidden Markov Model

Using historically labeled data (i.e., data where money laundering activities are already flagged), we will train the HMM to learn the transition and emission probabilities.

4.1 Using Baum-Welch Algorithm

The Baum-Welch algorithm estimates the transition and emission probabilities of hidden Markov models (HMMs). This algorithm iterates through the data, adjusting the parameters—transition and emission probabilities—to maximize the likelihood of the observed data.

4.2 Train the HMM Model

Step 5: Prediction and Evaluation

After training, the HMM can be used with new, unseen transaction data to predict if the transactions are part of a money laundering operation.

5.1 Prediction of Hidden States

For a given sequence of observed transactions, apply the Viterbi Algorithm to predict the most likely sequence of hidden states (i.e., the likelihood of the sequence of transactions belonging to legitimate or suspicious activities).

5.2 Anomaly Detection

Any sequence of transactions that involves unusual patterns, such as:

5.3 Evaluation Metrics

Assess the model using metrics such as:

Implement cross-validation using historical data that includes labeled suspicious and non-suspicious transactions to evaluate the model’s effectiveness.

Financial institutions have recognized that unless sophisticated AI analytics are employed in the effort to identify money laundering transactions linked to human trafficking, overcoming this battle is challenging.

They must collaborate with technology firms to share their use cases and enable data scientists and technologists to deploy advanced AI models to mitigate these ML risks.

This will assure regulatory bodies and committees that financial institutions are prepared to proactively identify and prevent heinous crimes, providing crucial protection to individuals from trafficking—a significant service to humanity.

Venkatesh Balasubramaniam

CAMS, CFCS, DMTS – Senior Principal Member, Consulting Partner, Head – BFSI Consulting, Americas Hub, Global Head – Financial Crime and GRC Practice

Venkatesh is an experienced BFSI consulting leader with more than 28 years of corporate experience. He specializes in banking regulatory compliance and brings extensive experience in technology consulting and transformation across areas such as fraud, AML, KYC/CDD, sanctions, GRC, and compliance regulatory reporting.

He is a Senior Principal Member in Wipro’s Distinguished Members of Technical Staff (DMTS), focused on building AI/GenAI/Agentic AI solutions to address customers’ business and technology challenges.

Joydeep Sarkar

Senior Architect – Blockchain, AI/ML

Joydeep is a senior architect with over two decades of experience in distributed and decentralized computing, as well as artificial intelligence. He is also a Principal in Wipro’s Distinguished Members of Technical Service, focused on building AI/ GenAI engineering solutions.

Dr. Gopichand Agnihotram

Director, Wipro Innovation Network (WIN)

Dr. Gopichand brings over 19 years of experience in artificial intelligence and machine learning to his role. He also serves as a Principal Member of the Distinguished Technical Staff at Wipro. A prolific innovator, he holds more than 40 patents and has authored over 50 publications in esteemed platforms such as Springer and IEEE. His impactful contributions to the fields of AI and ML underscore his deep expertise and unwavering commitment to advancing the frontiers of technology.